Formulas that appear in this note is also noted here Formulas.

The of a Reaction

Chemical kinetics is the area of chemistry concerned with the speed or rate at which a chemical reaction occurs.

It is called chemical kinetics because it literally refers to the movement or change ( kinetics ) of a chemical reaction.

A central concept in chemical kinetics is the reaction rate of a chemical reaction.

We can all express chemical reactions simply as such:

This expression shows us that over a course of time, the reactants involved are consumed to forms the products.

This observation means we can do the following:

- observe the decrease in concentration of our reactants; and

- observe the increase in concentration of our products.

With this in mind, we can rewrite our expression using the concentration of our reactants ( ) and the concentration of our products ( ).

This rewritten expression allows us to create expressions for their rates in terms of concentration per unit of time ( seconds ).

In these expressions, the terms and refer to the change of their respective concentration; divided by the change in time or the time elapsed ( ).

In the first expression, is a negative quantity because it decreased in concentration, therefor a negative sign is added to make the rate positive; unlike the second expression where is a positive quantity because it increases with time.

Overall Reaction Rate

If we are given the following chemical reaction:

We can make the following observations:

- 2 moles of reactant is consumed;

- 1 mole of product is formed;

- reactant reacts twice as product ;

With these observations, we can determine the overall reaction rate ( ) of our reaction as such:

So if we were given this general reaction:

we can get this general expression:

Other Means to Measure Reaction Rate

Depending on the nature of your reaction, other means and methods to measure reaction rates become available.

For example: in an aqueous solution, molecular bromine reacts with formic acid ( ) as:

Molecular bromine is reddish brown and all other species present in the reaction are colorless. As the reaction progresses, the concentration of steadily decreases alongside its color.

In this scenario, the reaction rate can me measured with the use of a spectrometer. In this reaction, we can plot the concentration of bromine versus time; and the reaction rate is the slope of our tangent ( ).

If one of our products or reactants in a reaction is a gas, we can use a manometer to determine the reaction rate. We can do this using a modification of the Ideal Gas Law:

We can modify it further to be used in determining molarity:

with this final equation, we can turn our concentration ( ) into a reaction rate ( ) and our pressure ( ) into pressure per unit of time ( ):

The Rate Laws

One way to study the effects of reactants concentration ( ) is to measure its relationship with your reaction’s initial reaction rate ( ). We measure the initial rate because as the reactant concentrations decreases over time it may make the measurement of the rate difficult.

If given the following reaction:

Alongside the following table of data:

| Experiment | Initial Rate ( ) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||

| 2 | |||

| 3 |

With the data table below, we can observe the following:

- in experiment 2, we can observe that when we quadruple while keeping the same, our initial rate is also quadrupled;

- in experiment 3, we can observe that when we keep the same while doubling , our initial rate is also doubled;

From our observation, we can make the claim that the initial rate is proportional to both its reactants’ concentrations.

This expression can be turned into an equation if we add a rate constant ( ).

The rate constant is a constant of proportionality and is added for the case where the product of reactant concentrations does not equate to the rate.

The previously given equation is not enough to apply to all reactions, because the weight in changing a reactant’s concentration varies. In simpler terms: changing the concentration of one reactant affects the rate more than changing the concentration of the other reactant/s.

This is why the proper generic rate law has the exponents and as the reactant’s respective reaction orders.

If all right-hand values are known ( , , , , ), then we can calculate the rate of our reaction using the rate law.

Case: Reaction Orders are Unknown

When given a reaction where your reaction orders are unknown, we can use the following formula below:

Generic Rate Law - Reaction Order Formula

Link to original

- Use case:

- For calculating the reaction order of a reaction using the generic rate law;

- Use two sets of experimental data where the values of the other reactants are equal on both experiments.

- Variables:

- - Reaction order of reactant;

- - Reaction rate of your first experiment ( )

- - Reaction rate of your second experiment ( )

- - Concentration of your reactant in the first experiment ( )

- - Concentration of your reactant in the second experiment ( )

- Formula:

If your reaction has two or more reactants, repeat the process for each reactant to obtain all reaction orders.

Case: Rate Constant is Unknown

In a scenario where all values are known except for your rate constant, use the following formula below:

Generic Rate Law - Rate Constant Formula

Link to original

- Use case:

- For calculating the rate constant of a reaction using the generic rate law;

- use one set of experimental data;

- Variables:

- - Reaction rate constant;

- - Reaction rate ( )

- - Concentration of first reactant ( )

- - Concentration of second reactant ( )

- - Concentration of nth reactant ( )

- - Reaction order of your first reactant ( )

- - Reaction order of your second reactant ( )

- - Reaction order of your nth reactant ( )

- Formula:

Overall Reaction Order

When using the rate law to calculate different values, it is essential to know what your reaction’s overall reaction order.

A reaction’s overall reaction order is calculated using the formula below:

Overall Reaction Order Formula

Link to original

- Use case:

- For calculating the overall reaction order when all reaction orders are known.

- Variables:

- - Overall Reaction Order;

- - “the sum of all—”;

- - reaction order; the exponent of your reactant’s concentration

- - first reactant’s reaction order;

- - second reactant’s reaction order;

- - nth reactant’s reaction order;

- Formula:

The Unit of the Rate Constant

Unlike other variables, the reaction rate constant ( ) has a unit that changes depending on your reaction order.

To get your appropriate unit, you can use the formula below:

Rate Constant Unit Formula

Link to original

- Use case:

- For determining the unit of your rate constant ( ).

- Variables:

- - Overall reaction rate;

- Formula:

Or refer to the table below:

| Overall Reaction Rate | Rate Constant Unit |

|---|---|

| 0 ( zero-order reaction ) | or |

| 1 ( first-order reaction ) | |

| 2 ( second-order reaction ) |

Relation Between Reactant Concentration and Time

Since the rate laws allows us to calculate the rate of a reaction from its rate constant and reactant concentrations, we can also modify the equation to calculate the concentrations of our reactants at any time during the course of a reaction.

Reactions are classified into orders depending on their overall reaction order, which can be calculated by summing up all of the reactants’ reaction orders;

Below is a table containing all the reaction-orders, their rate laws, their concentration-time equations, and their half life equations;

| Order | Rate Law | Concentration-Time Equation | Half-Life |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | |||

| 1 | |||

| 2 |

Activation Energy and Temperature Dependence of Rate Constants

A lot of things in our every day life has its process sped up or slowed down in relation to temperature; for example: much less time is required to hard-boil an egg at higher temperatures, and food stored in cold and low temperature environments take more time to go bad.

This truth also applied to reactions; the reaction rate constant of your reaction is dependent on the initial temperatures.

The Collision Theory of Chemical Kinetics

The kinetic molecular theory of gases states that gas molecules move and collide with one another frequently, it is also safe to assume that chemical reactions occur per collision between reacting molecules.

In collision theory of chemical kinetics, we expect the rate of a reaction to be directly proportional to the number of molecular collisions per second or to the frequency of molecular collisions:

But is it necessary to note that not all collisions lead to reactions; calculations on kinetic molecular theory show that at ordinary pressures and temperature ( and ) there are about binary collisions ( collisions between two molecules ) in of volume every second, in the gas phase, and even more occur in liquids. If all binary collisions led to a product then all reactions would be instantaneous, but they are not in reality.

Any molecules in motion, such as gases, possess kinetic energy; the faster they move, the greater the kinetic energy. Upon the collision of molecules, part of their kinetic energy is converted into vibrational energy.

If the initial kinetic energies are large then the colliding molecules will vibrate so strongly as to break some of their chemical bonds. This bond fracture is the first step that leads to product formation. On the other hand, if the initial kinetic energies are weak, the molecules will simply bounce off each other.

Energetically speaking, there is some minimum collision energy below which no reaction occurs.

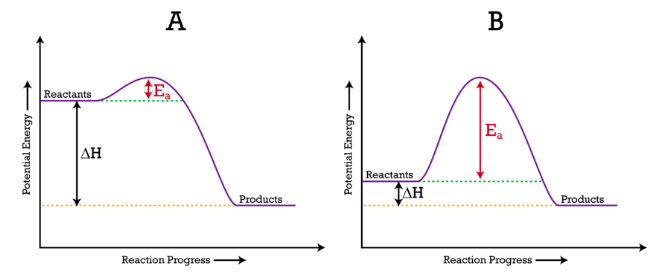

We postulate, that in order for reactions to occur during molecular collisions, the molecules must have an equal or greater amount of activation energy ( ) in order to exhibit reactions upon collisions; energies below this threshold will leave the molecules intact and no change resulting from the collisions. The species temporarily formed by a binary collision of reactant molecules before a product if formed is called the activation complex or transition state.

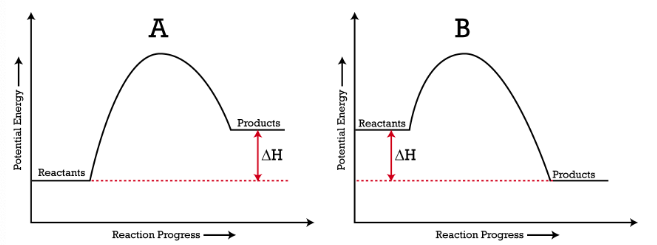

In the given graphs above, the following can be observed:

- If the reactants has less potential energy than the products, then after reaching the transition state, the reaction will retain some of the energy from the activation energy ( ); this is an endothermic reaction;

- If the reactants has more potential energy than the products, then after reaching the transition state, the reaction will release the excess energy from the activation energy ( ); this is an exothermic reaction;

In the given diagram, we can see a noticeable hill in our graph, this is our activation energy barrier; the shorter the height of your activation energy barrier, the faster the reaction will take place.

Reaction Mechanisms

As you may have learned from this note, and from prior knowledge: reactions are a process and are not instantaneous.

Chemical formulas are a great way to express that your reactants change into your products, but it can be misleading in the sense that it only shows your origin ( reactants ) and your destination ( products ). The best way to visualize a reaction is as a route from your origin to your destination; it’s not necessarily a straight line— it can have turns and crosses —in a reaction, these are called elementary steps and your total route is the reaction mechanism.

For example, for the formation of nitrogen dioxide ( ), we assume that it is just the collision of 2 nitrogen monoxide ( ) molecules and an oxygen molecule ( ) because that would make for a balanced equation; but this cannot be true because during the course of the reaction, dinitrogen dioxide ( ) is detected. With the presence of in mind, we can define the reaction as two elementary steps:

Elementary step 1 - nitrogen monoxide molecules collide to form dinitrogen dioxide

Elementary step 2 - dinitrogen dioxide molecules collide with oxygen molecules to form nitrogen dioxide

Now with the both our elementary steps formulated, we can make the overall reaction formula below:

Notice how is present and cancelled on both sides, this is because it is called an intermediate. Intermediates are species that are present in the reaction mechanism but not in the overall reaction equation. Intermediates are always formed in early elementary steps and are consumed in later elementary steps.

The molecularity of a reaction is the number of molecules that appear during an elementary step; the molecules may be of the same or different types.

The two elementary steps before are considered bimolecular reactions, because they involve the collision and reaction of two molecules ( two molecules of ; and ).

Unimolecular reactions— elementary steps involving one molecules —and termolecular reactions— elementary steps involving three molecules —also exist.

Rate Laws and Elementary Steps

Knowing the elementary steps of a reaction can help in identifying and deducing the rate law of a given reaction.

For example, we have the following general elementary reaction:

The fact that there is only one molecule present, we can confidently say that this is a unimolecular reaction. The reaction progresses faster the higher the number of A molecules present. Thus we can conclude that the rate is proportional to the concentration of A, or is first order in A:

For bimolecular reactions, say we have the following general elementary reaction:

This reaction is affected by the frequency of which A and B collide, which means that the rate is proportional to concentrations of both A and B; we can express the rate law as a second order reaction of two molecules:

Another variation of a bimolecular second order reaction is the following:

This gives us a reaction rate law of:

The example above show that a reaction order for each reactant in an elementary reaction is equal to its stoichiometric coefficient in the chemical equation for that step. Generally, we cannot tell merely by looking at the overall balanced equation whether the reaction occurs as shown or as a series of steps. We can determine this in the laboratory.

Whenever we study a reaction with more than one elementary step, the rate law for the overall process is given by the rate determining step, which is the slowest step in the sequence that leads to product formation.

An analogy for the rate-determining step is the flow of traffic along a narrow road. Assuming the cars cannot pass one another on the road, the rate at which the cars travel is governed by the slowest-moving car.

When conducting experimental studies of reaction mechanisms, we start with a rate measurement. Next we analyze the data to obtain the reaction rate orders and the reaction rate constant, we then write the final rate law. Afterwards, we suggest a plausible mechanism for the reaction in terms of elementary steps.

The elementary steps must satisfy both requirements:

- The sum of the elementary steps must give the overall balanced equation for the reaction.

- The rate determining step must predict the same rate law as determined experimentally.

Catalysis

To be added

Key Definitions

- Reaction rate

- the rate of a reaction measures how fast a reactant is consumed or how fast a product is formed;

- the unit of rate is expressed in molars per unit of time ( , molars per second );

- Overall reaction rate

- the reaction rate of the entire reaction;

- can be determined by dividing the reaction rate of the reaction’s product or reactant by its respective coefficient;

- Reaction order

- the influence that a reaction’s concentration gas on the reaction rate;

- Rate constant

- the proportionality constant that exists in all generic rate law equations but with varying value;

- its unit varies and depends on the overall reaction order of the reaction.

- Rate laws

- due to experimental data, rate laws were made to express the process in simpler terms;

- it is expressed as the relationship of the rate constants, concentration, and rate order;

- rate laws are used to determine concentration after a set amount of time as well as a reaction’s half life;

- Temperature dependence of rate constants

- in reactions, equal or greater reaction energy is needed;

- rate constants is directly proportional to the temperature;

- Activation energy

- The minimum amount of energy needed for molecules to have reactions upon collision;

- Reaction mechanism

- the sum and/or series of elementary steps taken for the reactants to turn into products;

- Elementary steps

- intermediary steps taken during a reaction.

- Intermediate

- a species that appears in the reaction but is excluded from the overall chemical formula;

- a species that appears in early elementary steps and are consumes in later elementary steps.

- Molecularity of a reaction

- the number of molecules involved in an elementary step; molecules can be of the same or different types;

- can be unimolecular, bimolecular, or termolecular;

- Unimolecular reactions

- elementary steps involving one molecule;

- Bimolecular reactions

- elementary steps involving two molecules;

- Termolecular reactions

- elementary steps involving three molecules;

- Rate determining step

- the slowest step that determines the rate law of the entire reaction;